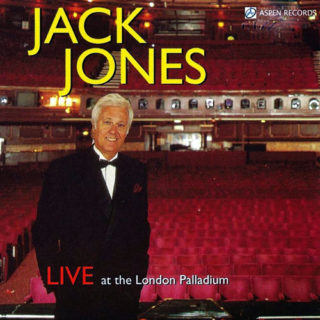

Jack Jones, who began his singing career in the late 1950s, will perform a celebration of his 80th birthday Saturday at the McCallum Theatre in Palm Desert. Rick Darius/McCallum Theatre

Frank Sinatra was never shy about measuring up his fellow singers.

Tony Bennett was the heir apparent. But of the male vocalists born in the two decades after his birth in 1915, Sinatra had great things to say about Sammy Davis Jr., Vic Damone, Jerry Vale, Buddy Greco, Steve Lawrence and Jack Jones.

Jones, who performs Saturday at the McCallum Theatre to celebrate his Jan. 14 80th birthday, never knew exactly how Sinatra sang his praises until a British fan sent him a Guy Harwood book, titled “Sinatra On Sinatra,” containing a 1965 quote from him.

Jones had just won his second Grammy Award when Sinatra said, “Of the male newcomers, Jack Jones is the best potential singer in the business. He has a distinction, an all-round quality that puts him potentially (italics included) about three lengths in front of the other guys. He sings jazz pretty good, too. But he’s got to be handled very carefully from here on out. The next year is going to tell.”

History will judge if Jones maintained that three-length lead in the race to succeed the world’s greatest male jazz-pop singer. But, with his rivals deceased except for Bennett and Lawrence, the Indian Wells resident recently joked that his ambition now is “to be the world’s greatest singer by default.”

That’s where we began an interview on his seven-decade career, following his recent return from a 14-date tour of the UK that Jones said will be his last big British tour.

THE DESERT SUN:I love your line, “My ambition is to be the world’s greatest singer by default.”

JONES: Yeah, you know, Tony (Bennett) is still with us and doing great, but somebody said, “There’s only one left, and then there’s you.” So I said, “Yeah, my ambition is to be the world’s greatest singer by default.” But there are a lot of great singers that do that same kind of music that are younger than me. It’s just a silly comment.

Did the recent death of Vic Damone (who once lived in Indian Wells) affect you?

Yeah. The fact that I didn’t know about it until I got home. We had a mutual admiration society. He always said I had the best “set of pipes” and I said the same thing about him. There was a time when Rena, his wife, was begging us to talk to Steve Lawrence to go out (on the road). With Vic and myself, it would have been one hell of a tour.

That Sinatra quote could be an albatross. When he says you have potential, it’s more than praise. It’s putting expectations on you. Did you feel pressure from it?

No because I was very young and optimistic. I was thrilled that he said that. But he was retiring when (that book came out). My line as a joke was, “But the son-of-a-gun didn’t retire!”

Your early manager, Jack Leonard, was Sinatra’s predecessor in the Tommy Dorsey big band. You say in your act he taught you how to sing a love song by telling you to get a girlfriend, and then she had to dump you and break your heart.

He really said that. It was good advice. You have to learn what the words mean or you’re just singing them, you’re not acting them out. (But) that was way early on. Nick Sevano (a Sinatra friend from childhood) was my manager while all that was going on.

How did Sevano help you?

He presented himself almost as Frank Sinatra’s manager. He was great with malaprops. He’d say, “You don’t want to mess around with that guy. He’s in another cloud.” Just a little off. It seemed the right place to be. It was a Sinatra singer’s world I was coming into, so, he was helpful, I guess. He wasn’t an intellectual and there came a time when the best kind of manager to have was an intellectual one.

We’re talking about 1962 or ’63. Did Leonard and Sevano influence you to go down the Great American Songbook road, or was that your father (light opera singer Allan Jones)?

My father didn’t. He hated what I was doing and he was not thrilled that I would come home every day and listen to Sinatra. One particular album I listened to all the time, and in my opinion it’s the greatest ballad album ever made, was “Only the Lonely.” I would listen to that all the time, which kind of makes me feel I was a disturbed child.

Certainly a depressed kid.

My first demo had four songs recorded with the Page Cavanaugh Trio. A songwriting friend of ours, Don Ray, who wrote “I Remember April,” put up the money and said, “I want people to hear you.” And he sold me to Capitol Records. I played the demo for my dad and he said, “I don’t like the demo. You shouldn’t be singing like that.”

How did you feel about rock and roll?

When you’re striving to do what I was trying to do, rock and roll was probably a nuisance. But then it became the way of life that the world was going. I didn’t know rock and roll would (become the messenger of the youth culture). Rock and roll was banned from television for years. Guys like me did a lot of guest shots on people’s shows because they couldn’t book rock and roll singers.

In 1962-’63, Sinatra was running Reprise Records, but he wasn’t getting hits from his standards singers. He had success with (folk-rocker) Trini Lopez, so it didn’t seem so much a Sinatra singer’s world. It was more of a rock and roll period.

That was the interesting thing about my timing. By this time, I was with Kapp Records. The reason Capitol let me go, they were trying to make me into a rockabilly singer, something I wasn’t. But, Dave Kapp had this steadfast course he was on about great songs. So, in the middle of this dawning of rock and roll, here comes Jack Jones singing “Lollipops and Roses,” which is pretty vanilla, but appealing to women. It was a big hit. But that was the furthest thing from rock and roll that you could get.

You must have always had a good voice. Was Capitol ignoring that to make you into a rockabilly singer?

Yeah. Because they knew better than I the way the business was going. However, when I was heard in a nightclub in San Francisco, Pete King (of Kapp Records) made a call to New York and said, “I think I found a boy singer for the label.” Dave Kapp agreed and signed me. Kapp found some great hits for me. I recorded (Sinatra’s smash) “Strangers in the Night” first. I happened to open my stupid mouth after I finished recording it. I went across the street and I saw (Sinatra producer) Jimmy Bowen. He said, “What have you been doing?’ I said, “I just did a session.” “Oh, anything any good?” “Yeah, I did a song I think is a hit. I don’t particularly like it, but I think it’s a hit.’ I told him what it was and, a day-and-a-half, two days later Sinatra was in the studio recording it.

He hated it, too, but it was a (1966) hit.

Yeah. He did that “Do-Be-Do-Be-Do” at the end because he was bored with it. And they kept it in. Mine was very straight, very nice, but I don’t think it was a good record the way we did it. My company put “The Impossible Dream” out with “Strangers in the Night” on the B side. “The Impossible Dream” was a great record. But, when they found out I had it on the B side, (Reprise was) ready to go. In his book, Bowen made fun of me for being stupid, and I was stupid, but I didn’t like him for saying so.

This was after you had a hit with “Call Me Irresponsible,” which Sinatra recorded first. Do you think the fact that your version of “Call Me Irresponsible” outsold Sinatra’s made them more attentive?

Yeah, that’s why.

Any other regrets you wish you could do over?

We call them sob stories. Yeah, I’ve got a couple. I was producing an album in Hollywood for RCA. Mike Berniker was head of A&R for the label in New York. We were working together on the phone and I found this song and opened the album with it. I called Mike and said, “This is a hit.” He said, “No, it isn’t.” I said, “I swear to you, it’s a hit.” He said, “Nobody wants to release it” and that was the end of that. Then, a year later, the guy who published it wrote me a letter and said, “Jack, I’m sorry. I waited a whole year and I know this song is a hit, so I’m doing it with another singer.” So, he used my record as a demo to the other singer, and the song went like this, “So I sing you to sleep, after the lovin’” (which became a comeback hit for Engelbert Humperdinck in 1976). Now that’s a sob story.

The other one is, I had a piano player who was a bit finicky. There was a song that was not a difficult song; he just didn’t want to play it. So, we put it on the shelf. It was a Burt Bacharach song and it went, “You see this guy, this guy’s in love with you” (which became Herb Alpert’s first vocal hit in 1968).

When The Beatles came along in 1964, everybody suddenly had to write their own songs. The Rolling Stones’ manager, Andrew Loog Oldham, famously put Mick Jagger and Keith Richards into a room and told them not to come out until they had written a song. Did anybody try to push you into songwriting?

No. I’ve written quite a few songs. I’m good at rhyme and I’m good at writing parodies, or special lyrics (his special lyrics to “I Am A Singer” brought Sinatra to tears when he sang them at a 1990 Society of Singers tribute).

Did you find it more difficult to find songs you wanted to sing after The Beatles?

I didn’t equate it to The Beatles coming along. It just became a reality that people were not writing for singers like me. I tried doing some things that were not (Great American Songbook). Even Sinatra did. He was forgiven because he had more clout to recover. But he did some really dumb songs.

It also inspired him to do Brazilian music, which was a great addition.

That is right, and that’s something I always wanted to do. There’s one I’m doing in this show from “Black Orpheus,” “A Day in the Life of A Fool.” That’s (Antonio Carlos) Jobim.

Yeah, there were international songwriters that weren’t getting exposed in America, like Jacque Brel. You found Michel Legrand (for 1993’s “Jack Jones Sings Michel Legrand” with lyrics by Marilyn and Alan Bergman). How did you find your songwriters?

I forgot how that happened, I just know we went to Paris and worked on the album for two weeks prior to recording it. I just stood in the middle of this orchestra. They didn’t know me, I didn’t know them and we just started to bond. It was a fantastic experience. I came home to RCA and I actually mixed my voice too far back because I was so in love with the orchestra. That’s where I met the Bergmans. They came down and I said, “There’s only one vocal I’m not happy with. Do you want to produce it with me?” So we did, “What Are You Doing For the Rest Of Your Life.”

I just interviewed Lorna Luft and she said she didn’t return to the Great American Songbook until (singer-musicologist) Michael Feinstein made it cool again in the 1980s. Did you see that music become cool again and did that affect you?

It’s something I never really thought about. In my life, I’ve just done what I’m supposed to be doing. A few times I tried to be something I’m not, but, I just enjoy what I’m doing. It might have been cool if I had done duets with younger people, but I didn’t. I’m now 80 and I can look back, but I don’t know about a historian coming along and making things cool again. Michael’s a great talented guy and we’re friends, but, I don’t know.

You became more jazzy in the ‘90s. Was that because it was suddenly OK?

I just did it because I always wanted to do it. My group is (comprised of) really good jazz players (led by pianist Christian Jacob with Hammond B3 organist Bill Lowden) and we make really good music. We’re not saying it’s jazz, it’s inventive.

This year we’ve seen Neil Diamond retire because of Parkinson’s and Paul Simon and Elton John announce their end of touring. Can you see yourself stop touring?

I can’t see myself doing what we just did. We covered 3,000 miles and there were people who didn’t miss a show. It was wonderful. But the traveling is getting harder and the world is getting angrier, so I would do what Tony does. If Tony goes to England, he does a couple venues and leaves. If I went out for a week in the States it would be fine — as long as I’m singing well, and in some ways I’m singing better than when I was a kid. It’s just, flying is something I hate.

What about singing locally? You used to sing at The Nest.

(Nest co-owner and pianist) Kevin Henry is a very dear friend of mine. He’ll start playing “Me and Mrs. Jones” and I’ll sing it with him and I’ll sing it to my wife. This is my home town and that’s my neighborhood pub.

(Saxophonist) Tom Scott has talked about how you stole his show when you got up and sang with him at Pete Carlson’s (Golf & Tennis).

That’s ironic. You know that blues album you always said I should do? Tom and I are going to do it. That’s one of the things I’m going to do when I stop traveling.

That’s great! What about this show at the McCallum? Will you do anything special for your 80th birthday?

We’ve been doing what was a new show for England. There will be some old stand-bys. The “La Mancha” thing will be in there because people really want to hear that. Now, when I sing “The Impossible Dream,” the words are even more meaningful.

Jack Jones in concert

When: 8 p.m. Saturday

Where: McCallum Theatre, 73-000 Fred Waring Drive, Palm Desert

Tickets: $37-$87

Information: (760) 340-ARTS, mccallumtheatre.com